Early on in my beer writing career, I attended an incredible dinner at a barn in West Michigan hosted by Brewery Vivant and New Belgium Brewing Company.

It was an incredible dinner by two great breweries. More importantly, it began my relationship with Jason and Kris Spaulding, the owners of Brewery Vivant, who are simply incredible people. Prior to opening Vivant in 2010, Jason was one of the co-founders of New Holland Brewing Company, certainly one of the pioneers of the Michigan craft beer scene.

Jason was often a regular source for me when reporting stories on the beer industry; he was plugged in, knew the industry like the back of his hand, and could, with relative ease, see where it was headed.

Now, as I look around and have no real idea where the industry is going, I turn to brewery owners like Jason to say, “What’s happening?” And when they also don’t know, it’s a curious situation.

The Spauldings recently rebranded Brewery Vivant to Vivant Brewery & Spirits to better align with what customers are now looking for. And that provided me an opportunity to chat with Jason about where the business is and where the industry might be headed.

Also in this issue:

Literary Libations

Good reads of the week

What we’re drinking

Beer world changing as we speak

When Brewery Vivant opened its doors in 2010, there were roughly 2,000 breweries in the United States.

It was so many more than the less than 80 there were in the 1970s, but far fewer than the 10,000 or so open now, 14 years later. At the time Vivant opened, the craft beer surge was just beginning, and there was palpable excitement about the industry and the beers.

Brewery Vivant was a neat addition to the Grand Rapids beer scene and was unique in so many ways, with a focus on French and Belgian-style beers and a French countryside-inspired food menu. Owners Kris and Jason Spaulding set out to create an anchor for the East Hills neighborhood in Grand Rapids and more than succeeded with another eye toward being a sustainable business in every conceivable way.

Jason was a founder of New Holland Brewing, a Michigan brewery that popped up in the short beer boom of the 1990s and helped set the stage for the surge that happened in the 2010s. When both New Holland and Vivant opened, there was a push to get people to try beer, to know there was more than light lagers and Guinness.

There is no doubt that craft beer rocketed past that and gained a significant chunk of market share in the beer world, but the growth has slowed, and the excitement has deflated. Beer production and imports were down 5% in 2023, with craft brewer sales declining by 1%, according to the Brewers Association. In 2023, small and independent beer made up 13.3% of U.S. beer market, well above the 5% or so it was when I began writing about the industry back in the early 2010s.

“It was a small industry, we always joke around that it was asshole-free, because it's all so small, but people that were in it were in it for the passion of beer,” Spaulding said. “And we're up against these huge obstacles, fighting these big breweries and and our goal really was just to get people to recognize theres beer with more flavor. We had a really small piece of the market, but that piece of the market was super excited and enthusiastic.”

But as the fever caught on and people looked to the growing number of breweries to keep pumping out new innovative beers, the thirst for novelty became regular. And with 10,000 breweries now making liquid, all while new products like ready-to-drink cocktails, hard seltzers, CBD drinks, etc., the deluge is nonstop and the shelves are more stocked than ever.

Major breweries grew before selling off, such as fellow West Michigan breweries Founders and Bell’s. And now we see true commercialization come and watch business people change the model of how craft beer works.

While major brewing corporations can weather the wholesale storm, the smaller neighborhood breweries are struggling with oversaturated shelves and the struggle to stand out as consumers look for something new. For Vivant, Spaulding said they’re selling approximately a third of what they sold wholesale in 2019.

That’s an interesting predicament for all these companies that invested in their production facilities during the rise, especially the ones who helped establish the base like Vivant. Is it an indication of something these breweries are doing wrong? Not at all.

Take Anchor Steam, for example. The epitome of craft beer pioneer. A classic beer brand with an incredible flagship and plenty of great beers alongside the classic. But, somehow over the years it was left behind and not long after Ballast Point Brewing (it’s own incredibly sad story) sold for $1 billion, Anchor was acquired for just $85 million by Sapporo. Then it continued a dip and eventually ceased operations before it was acquired this year by Chobani CEO Hamdi Ulukaya to restart the company.

“You think, like, Anchor Steam, yeah, I love Anchor Steam. I have good memories of that,” Spaulding said. “And then someone asked me when the last time I bought one? Ah, 10-15 years ago.”

It’s not because you don’t like the beer or the brand, it just gets lost in a lot of noise and the companies struggle in that noise. And that noise is louder than ever with 10,000 breweries. Which makes the neighborhood aspect of Vivant, and so many of the breweries across the U.S., all the more important.

And that’s partially why Brewery Vivant transitioned to Vivant Brewery and Spirits this summer. Fewer people walk into the brewery excited that the beer is made there, for many, it’s simply a restaurant that happens to make its own beer. Gone are the days when people were excited to see the brewing equipment through windows in the taproom. (In fact, the Spauldings have opened up two other restaurants, both Broad Leaf Brewery and Spirits, which have their own beer, but not brewed on site, and as Jason says, no one seems to mind.)

“We're still a neighborhood restaurant, which is not far off the mark from what we wanted,” Spaulding said. “But, increasingly more, people will just eat the food and they're not interested in the beer. And because that pie is bigger, you have to try to appeal to different people. You get an eight top of people and at least one of those people doesn't like beer and another one would rather have a mixed drink.”

It’s not just the brewing industry that’s changed either. Restaurants across the country are dealing with issues, from staffing to inflation to just pure misunderstanding from consumers. The pandemic also shifted customer expectations and habits.

It’s certainly not just Brewery Vivant going through a time of changes. Almost every brewery is, and so many of the brewers who came into the industry with Jason have come and gone. Whether it’s the Mike Stevens and Dave Engbers at Founders who sold to Spanish brewing giant Mahou San Miguel, or Bell’s, which sold to Kirin. Those were staples in the easy going beer world that set the tone for what the beer industry meant.

Larry Bell, while he might have rubbed some people the wrong way, was among the Midwest’s first craft beer pioneers in the 1980s and for a long time appeared as though it would remain a family-owned endeavor.

“That was a big deal. I teared up, my wife and I had a moment, we couldn't really believe it happened, because that was a brewery, if there was a brewery that was against selling out … someone to follow in the industry you want to follow, you have to respect Bell's at least. That was a that was a shock and a big change.”

And with that business has come the full circle point of commoditization, when a 15-pack of an IPA can be had for $15, not unlike the years of simply having a few choices of a 30-pack of light lagers for $15. How does a brewery like Vivant make it in the wholesale world trying to present a value proposition with a four-pack of beer for $17.

At a 5% margin in wholesale, there’s little room for errors on the big market, which makes the idea of tightening up to a community brewpub all the more appealing. However, it’s certainly different from less than 10 years ago, when people wanted more and more choice on the shelves.

Whether its the major companies coming in and eating up the true craft breweries or people getting into the wrong industry, there’s definitely a different feel to the people in the industry. Is it all bad, of course not. But it’s let out some of the magic of beer.

“The reason our industry was asshole-free is because it was a bunch of passionate people,” Spaulding said. “And now, it's just following regular business principles, right? And it's, it's just different. It can be empty and sad.

“I love beer, I love the industry, and I love the people in it. It's hard to watch the industry commoditizing, but unfortunately, that’s where we are.”

Literary Libations

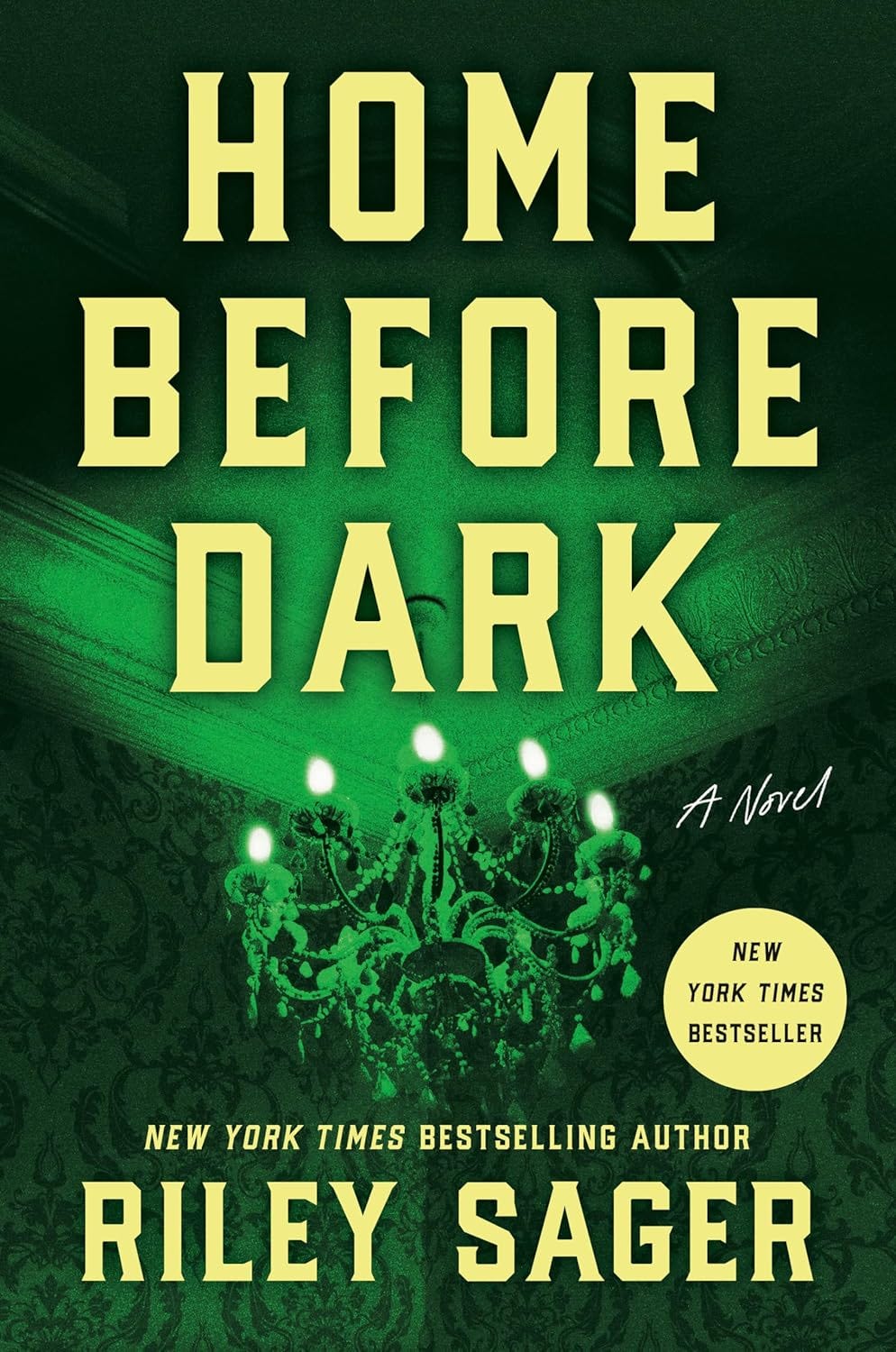

Hi readers and drinkers! This is Alyssa with your Saturday edition of Literary Libations, your go-to spot for book and beverage pairings. Spooky season continues this week, as I picked up Home Before Dark by Riley Sager. It’s a gothic real house of horrors taking place at Baneberry Hall, a creepy Victorian estate in the middle of the Vermont woods. It’s a dual-timeline, as Maggie Holt returns to her childhood home (of only 20 days) where her father based his international bestselling novel. I’m pairing the book with a Blood And Sand, a classic Scotch cocktail because doesn’t Scotch just scream FALL?!

¾ oz scotch

¾ oz vermouth

¾ oz cherry liquer

¾ oz orange juice (freshly squeezed if you’re feeling fancy)

Method: Add all ingredients into a shaker with ice. Shake that boy until you can’t feel your hands. Strain into a coupe glass. Drink up, crack open a book, and get spooked.

Interesting Reads of the Week

I’ve already mentioned this fall how much I love Oktoberfest beers. Well how did Oktoberfest become so big in the United States and why are there multiple festivals in each city? Fifty Grande dives in here.

I love museums. I love food. These are a bunch of cool museums about food! I think I’ll skip Iceland’s Herring Museum, but intrigued by Sweden’s Disgusting Food Museum. (Daily Passport)

What we’re drinking

I’m watching Notre Dame barely survive Louisville at the moment, so might as well bring back the Fighting Irish-branded Teeling Whiskey that inspired me to write about the booze and college partnerships a few weeks ago.

Also been sipping on Cognac Park Carte Blanche, a deliciously fruity cognac. I’m not sure why cognac hasn’t hit a big surge yet like bourbon and tequila, but I bet it’s coming!